Copyright is not fit for this digital age, and needs to be changed, so say two representatives of the Dutch national library in a letter to daily NRC yesterday. In their epistle (Dutch) Martin Bossenbroek and Hans Jansen, managers Collections & Service and E-strategy respectively of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (Royal Library), the Dutch national library, explain how difficult it can be to run large-scale digitization programs when for a large number of books it simply is not clear whether they have returned to the public domain or not:

Copyright is not fit for this digital age, and needs to be changed, so say two representatives of the Dutch national library in a letter to daily NRC yesterday. In their epistle (Dutch) Martin Bossenbroek and Hans Jansen, managers Collections & Service and E-strategy respectively of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek (Royal Library), the Dutch national library, explain how difficult it can be to run large-scale digitization programs when for a large number of books it simply is not clear whether they have returned to the public domain or not:

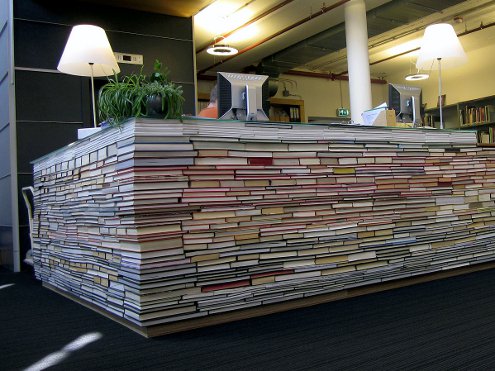

Copyright is a good thing, but the code that enshrines this right is too much of a good thing in its current form. In the digital age, it misses its targets. For hundreds of thousands of 20th century rights holders, it offers no protection, recognition and reward, but only the prospect of oblivion. An adaption of copyright law to the demands of the 21st century is needed urgently, otherwise the building of a digital library of any serious proportion will remain an illusion.

[Because of the difficulty of locating the heirs of long-dead authors, you cannot safely re-publish works that came out a 100 years ago.]

Both institutions and companies are keeping a safe distance from this copyright danger zone, and this will result in unbalanced digital collections. The digital library of the 21st century will have a gaping hole where works of that age should be. Hundreds of thousands of authors will never be found again. For them the chance of an epiphanous find followed by a second, digital life will definitely be gone.

This scenario can hardly be the meaning of a law that should protect an author’s rights. Before anything else, an author has the right to be read. That is why it is high time for an Internet exception for non-commercial use in the Dutch copyright law, one better thought through than the changes of 2004. Since then, heritage institutions are allowed to offer their collections electronically to the general public, but only from within their own building, using an intranet. That’s just not how the Internet works.

The authors go on about orphaned works, and how a mixture of Scandivian and Anglo-Saxon orphan works law could produce a best of both worlds: mixing extended collective licenses with the opt-out principle. Collective licenses, also known as levies, are funds paid by the public into one big pot, and redistributed to the copyright holders. In a lot of jurisdictions radio is paid for this way. This makes radio possible: if there were no collective licenses, a radio broadcaster would have to negotiate separate contracts with artists for each track they play. At least, so the theory goes. Opt-out means the author or their heirs has to state explicitly not to want to participate. Copyright law is opt-in by default, but stops functioning in areas where the rights holders cannot be traced, or only with immense difficulty. It is something authors have brought upon themselves with their support of the Berne Convention, which outlaws any sensible scheme for tracking authors and their works.

I published an essay on the same topic last week at the Teleread blog. Next week the Amsterdam public library will organise a conference on the meaning of copyright for libraries, where Ernst Hirsch Ballin, the Dutch Minister of Justice, will be one of the speakers.

Copyright is not fit for this digital age, and needs to be changed, so say two representatives of the Dutch national library in a letter to daily NRC yesterday. In

Copyright is not fit for this digital age, and needs to be changed, so say two representatives of the Dutch national library in a letter to daily NRC yesterday. In